SMOOSH JUICE

Retrospective: Dark Conspiracy

My history with roleplaying games is littered with games I desperately wanted to like but that, for one reason or another – sometimes many reasons – I simply couldn’t. A prime example of what I’m talking about is Dark Conspiracy, a near-future horror RPG released by Game Designers’ Workshop in 1991. Even now, more than three decades later, my feelings about Dark Conspiracy (or DarkCon, as it was often abbreviated back in the day) are complicated, so complicated, in fact, that I’m not entirely sure how well I’ll be able to articulate them in this post. Please forgive me if what follows is more rambling than usual.

Let’s start with some context. At the turn of the 1990s, the RPG world was in a state of transition. Arguably, that’s been the default state of the hobby since its inception, but I think it’s fair to say that, by the last decade of the 20th century, the times, they were a-changin’. Signs of the decline in the dominance of both Dungeons & Dragons and TSR were, by this time, becoming obvious and this created an opening for new games, new companies, and new approaches to roleplaying.

Of course, TSR wasn’t the only venerable RPG company to show signs of decline as the ’90s dawned. Game Designers’ Workshop was another one. Founded in 1973 as a wargames publisher, GDW nevertheless entered the roleplaying market quite early, when it released Traveller in 1977, only three years after the appearance of OD&D. However, by 1991, the fortunes of Traveller – and GDW along with it – were in doubt. Traveller was stuck in the doldrums of the Rebellion Era established by MegaTraveller and it was clear that something had to be done to reinvigorate the moribund game line. Likewise, history had caught up with Twilight: 2000. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 put into serious question the game’s speculative history of World War III, resulting in a second edition in 1990 that not only altered its timeline to bring it closer to reality but also changed its entire rules system.

Larger cultural shifts were also at play. The winding down of the Cold War, the rapid advance of computer technology, and the impending arrival of the new millennium fueled widespread anxieties. Some of these found expression in the cyberpunk genre, with its visions of corporate tyranny and technological alienation. Others surfaced in conspiracy theories about the New World Order, UFOs, and even apocalyptic religious prophecies. Like many turn-of-the-century moments, it was a chaotic, uncertain time, equal parts thrilling and unsettling. I was just entering adulthood then, and I remember the early ’90s with strange affection. On bad days, I find myself longing for those times.

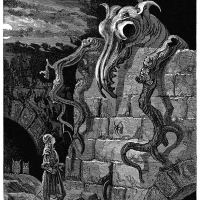

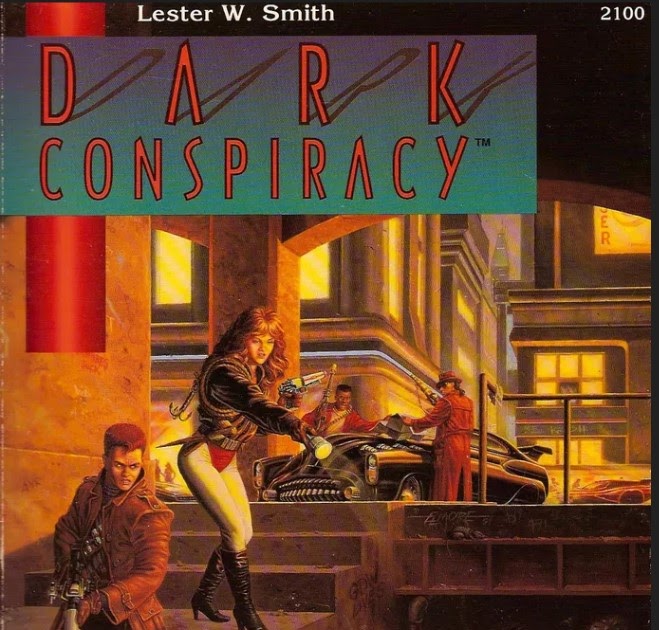

Enter Dark Conspiracy. Written by Lester W. Smith, Dark Conspiracy attempted to fuse cyberpunk’s dystopian corporate control with supernatural horror and alien invasion. At first glance, it seemed to be the perfect game for the era: a paranoid, near-future setting in which America had collapsed into vast urban metroplexes and lawless wastelands, while eldritch entities known as the Dark Ones manipulated humanity from behind the scenes. Thematically, it was an ambitious blend of Cyberpunk and Call of Cthulhu, a world where high technology coexisted with conspiracies, cults, and Lovecraftian nightmares.

In its published form, however, Dark Conspiracy was a game of contradictions. Its setting concept was rich and evocative, but its execution was often unwieldy. GDW, perhaps trying to draw on its existing fanbase, built the game’s mechanics on the same ruleset as the second edition of Twilight: 2000. While that system (which came to be known as the “House System”) worked well enough for military survival scenarios, it was clunky and a poor match for horror gaming in my opinion. Character creation was detailed but slow, leaning heavily on a career-based progression system that felt more suited to military campaigns than to the investigative horror that Dark Conspiracy promised. Likewise, combat was intricate – perhaps overly so – while supernatural and investigative mechanics felt like an afterthought by comparison.

Despite these flaws, Dark Conspiracy had undeniable strengths. Its setting, which painted a grimly fascinating picture of a broken America where the supernatural lurked at the fringes of perception, held a lot of possibilities, even if they were never fully realized. The game encouraged a mix of adventure styles, from corporate espionage to alien-hunting and post-apocalyptic survival. In some ways, it was ahead of its time, prefiguring the pop culture explosion of conspiracy fiction that would define the late ’90s and early 2000s. Remember that the genre-defining television series, The X-Files, wouldn’t air until 1993, two years after the publication of this game. People often use the phrase “ahead of its time” too casually, but, in this respect at least, Dark Conspiracy earns it.

The game never quite found its footing. GDW supported it with a range of supplements, including adventures and setting expansions that deepened its world, but they were uneven both in terms of quality and their portrayal of the game world. Some, for example, suggested that its early 21st century setting was not too dissimilar to the real 1990s but with slightly more advanced technology, while others implied much greater social and technological changes. Early promotional materials for the game in the pages of Challenge painted a very dark, even bleak, picture of the setting, where vast swaths of the world had been largely abandoned and given over to the Dark Ones and their human co-conspirators and minions. Unfortunately, the published game was inconsistent on this point, which hampered my enjoyment of it.

This is a great shame. As I mentioned at the beginning of this post, I really wanted to like Dark Conspiracy. In principle, it’s a perfect mash-up of lots of ideas and genres that are right up my alley – science fiction, horror, dystopianism, conspiracy theories, and more. The potential of the game is immense and, especially at the time of its original publication, it managed to tap into an emerging zeitgeist. If only it had been better – better rules, better presentation, better adventures – it’s possible that it could have made a bigger splash and helped lift GDW out of its doldrums. Alas, that was not meant to be and I’m left only with my conflicted feelings.