SMOOSH JUICE

Game Review: Adulthood, or Aiming for Maximum Impact | BoardGameGeek News

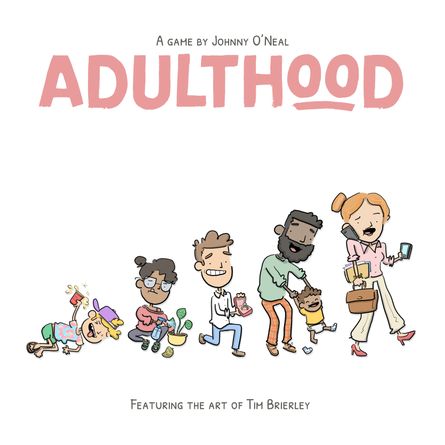

Aging isn’t a common tabletop game topic. We have ye olde The Game of Life, Funny Friends (although this is more about living your chosen life than aging), Cradle to Grave (in the most abstract way possible), and Adulthood, a 1-4 player game from Brotherwise Games‘ co-founder Johnny O’Neal that debuted in Q3 2024. (If I’m missing others, please let me know!)

Adulthood plants you in your late teens with a starter job and time: eight blocks of time, to be exact. Each round, you allocate that time to actions — career, leisure, wellness, etc. — then you get the results of those actions — money, happiness, energy, etc. — after you…acquire a card and play cards from your hand.

Okay, the thematic structure isn’t a direct match to aging given that any number of games fall into the pattern of assigning workers to gain resources that you use to do other stuff. The feel of aging — or more specifically, of growing up — comes through the use of card titles, text, and imagery, with cards like “Family Time”, “Protest”, “Social Media”, “Shoplifting”, and so on.

You start with one of two random careers in hand to give you some guidance, then you’re off. Each turn you assign time, money, and energy to actions (typically during other players’ turns), then you resolve everything, acquire a card, and play cards with the overall goal being to score impact and happiness. You move scoring markers on these tracks toward one another (as in Ark Nova), and once someone’s markers meet, you finish the round, then tally points: happiness + impact + endgame points that we’ll get into later – unhappiness – negative impact.

Now you might protest, saying “Just impact and happiness? There are other things that need to be taken into account here, like the whole spectrum of human emotion. You can’t just lump everything into these two categories and then deny everything else.” I would agree, but we’re in the world of game abstraction, with everything being boiled down into these two categories to streamline the game effects and give players focus…but what’s odd is that I’m not even sure that two categories are necessary because the difference between them in a multiplayer game is irrelevant beyond three specific cards:

These cards require you to score a particular attribute, but otherwise impact=happiness=1 point — which lessens the fun of what the design could be.

In contrast, Funny Friends, a 2005 design by Friedemann Friese and Marcel-André Casasola Merkle, has you track nine characteristics — how much you smoke, drink, eat, earn, read, etc. — and those characteristics affect one another: If you top out in smoking, you lose all your fat; top out in drugs, and there goes your money. You want to manipulate characteristics to reach goals; if you have the right levels of drinking and illness, for example, you can become a workaholic, which has the “bonus” of making you sad and breaking up a relationship — and that might be exactly what you need to achieve another goal.

Adulthood is more streamlined in its focus on two characteristics, but they’re essentially interchangeable, except in solo play when you have a goal of keeping either your impact or happiness as low as possible, which forces you to go heavy on the other side. I’m not rewarded in any way for being happier than other players or having my impact be twice my happiness — which means I can largely choose and play cards without regard as to whether I get impact or happiness. (Some cards give you red unhappiness or negative impact tokens, and those also function identically: lose 1 point per token from the characteristic in question, which translates to -1 point each from your final score.)

Admittedly, I’m focusing more on what I want than on what the game is giving. For example, the design is an open-drafting game in which you acquire one card each turn, ignoring what everyone else is doing and focusing on how well new cards mesh with what you are doing — which is not a style of game I appreciate. I want to have an impact on what others can do, but in this version of adulthood, my actions are important only to me, which is also true of my values.

Values are a fun thematic element, but until the end of the game, they’re only internally fun — that is, you keep them hidden, initially even from yourself.

You receive one value in hand and two face down during set-up, but by spending energy on a meditate action, you add a face-down value to your hand. You want to do this because you score all three values at the end of play, whether you know what they are or not, so you best get in touch with your inner self to determine what matters to you…although you can also meditate to ditch a value and gain a new one face down, akin to you moving the goal posts late in life to make your values match your actions rather than the other way around.

Values also come into play when choosing a partner. By spending time and money on the date action, you draw a new partner to your hand or (if you’re grown up) marry your current partner. Each partner has new actions for you to spend time on — one when you’re dating, another when you’re married — and at game’s end if your partner matches one of your values, you score 4 points.

How is a match determined? By seeing whether the teensy symbol on a value card matches the equally teensy hole in your partner’s heart. I had issues throughout my five games of Adulthood — once each solo and two-player, three three-player, all on a review copy — in seeing what was on my own cards, much less what was in front of others, which helped contribute to the game’s solo feel. The typeface on the cards is wee, and I had to pick up most cards from the market to read what was on offer.

These graphic design challenges were compounded by the apparent lack of a final edit on the cards and in the rulebook. A few cards use terms found nowhere else in the game, and the rules use blocks of text to explain gameplay instead of bullet points, making it harder to look up rules during play.

Another aspect I found lacking in the multiplayer game is that in addition to scoring values and (potentially) your partner at game’s end, you also score for sets of life icons, that is, the symbols in the upper right corner of many cards. The game uses eight life icons, and for each icon that you have at least three of, you score (the # of icons – 2) points, e.g., with four gem icons, I score two points.

Reading the rules, you might think that set collection will play a big part in your score, but in our multiplayer games we rarely had more than four of an icon, and we’d often end by counting “Two, two, two, three, two, three, two, two — okay, 2 points for icons”. Perhaps we were playing poorly, but you have no ability to manipulate the card market other than perhaps getting a second card through the effect of one played, so you’re somewhat at the mercy of chance. (You can use actions to draw more career and partner cards, most of which have symbols, and as you cycle through those, you place “discarded” careers and partners in your experience pile, so you might date someone just to get their service icon, then dump them immediately. How callous…)

In the solitaire game, you start by drawing two achievements, then choosing one, and trying to max out that card while also having your impact and happiness tokens meet. The market is three cards in each of eight rounds, with the cost to purchase additional cards escalating and with you being to flush and replace one of them. The solo achievements might have you trying to collect, say, creativity and fame icons, and the ability to grab more cards in one “turn” makes you feel like you have more control than in the multiplayer game.

Overall, Adulthood achieves what it’s trying to do, but for me the game would benefit from additional polish on the final production, as well as gameplay changes to make the difference between impact and happiness more meaningful. For more examples of gameplay and half of a solo playthrough, watch this video:

/pic8093627.jpg)

/pic8853600.jpg)

/pic8853572.jpg)

/pic8853587.jpg)

/pic8853605.jpg)

/pic8853637.jpg)

/pic8853715.jpg)