SMOOSH JUICE

Esoterica

My apologies to anyone not particularly interested in the Tékumel setting, which is the backdrop for my long-running House of Worms campaign. As this campaign races toward its conclusion after more than a decade of play, the stakes are rising. The characters are now uncovering some of the setting’s deeper mysteries—those that are either well hidden or not addressed at all in published materials. Fortunately, I’m both deeply familiar with Tékumel’s arcana and quite willing to deviate from it when doing so enhances the fun. That’s why I’m hopeful that the campaign’s final denouement will be a satisfying one.

In my most recent campaign update, I referenced several elements that may not be immediately clear or that deserve further explanation. Let’s begin with the Tsolyáni conception of the soul, which is largely inherited from the earlier Engsvanyáli civilization. According to this worldview, the soul is composed of five distinct parts:

- Bákte: the physical body, which is born, lives, grows, dies, and returns to dust.

- Chusétl: the “shadow self,” the sleeping counterpart of the waking person, which exists in dreams.

- Hlákme: the conscious mind, encompassing both intellect and ego: the “I-ness” of a person.

- Pedhétl: the bundle of raw instincts, lusts, fears, and desires, as well as the source of psychic power.

- Báletl: the spirit-soul, which travels after death to the Isles of the Excellent Dead before eventually being reborn.

Different gods and religious sects in Tsolyánu emphasize certain aspects of the soul over others. In the case of the Temple of Sárku, the Change deity of death, only the body and the intellect truly matter. Everything else is considered irrelevant. For Sárku’s worshipers, the intellect (or ego) is the essence of individuality, that which separates one person from another. Normally, this aspect ceases to exist upon death. The only part of the soul that survives is the Báletl, the spirit-soul, which is not truly individuated and is eventually reborn in someone else, without any memory of its previous existence. To a devotee of Sárku, this outcome is abhorrent. Thus, they embrace a sorcerous union of the body and intellect after death by becoming undead.

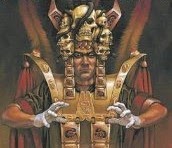

This is what makes Prince Dhich’uné’s plan, as described in the linked update, comprehensible. He seeks to ascend the Petal Throne, become emperor, and then offer his spirit-soul as a sacrifice to the pariah deity known as the One Other, because he sees no value in that part of his soul. Instead, he intends to preserve his body and mind as an undying emperor. This “exquisite gift” to the One Other, he believes, will secure for Tsolyánu a state of perpetual stability, allowing it to avoid the fate of all previous empires, including the ever-glorious Engsvanyáli Imperium.

Why does he believe this? Dhich’uné claims to have uncovered a dark secret: that the founder of the Tsolyáni Empire was a cultist of the One Other. The name of the first emperor is unrecorded; he is known only as “the Tlakotáni.” This name eventually became the clan name of the imperial line. However, anyone familiar with Engsvanyáli, the language from which Tsolyáni descends, knows that tlakotané means “brother,” but not in the familial sense. Rather, it denotes brotherhood in a priesthood or secret society. So, to which secret society did the first emperor belong? According to Dhich’uné: a cult of the One Other.

What evidence Dhich’uné has for this claim is not yet clear. However, the mystery surrounding the identity and nature of the first emperor is certainly suggestive. Moreover, although the worship of the One Other. like that of all pariah gods. is officially banned in Tsolyánu, his priests operate in secret within the Temple of Belkhánu. Even more curiously, they play a formal role in the emperor’s internment rites. Why, then, the public disavowal of the One Other, while simultaneously granting his priests a hidden role at the heart of imperial ritual? Dhich’uné believes he knows the answer: the empire was founded and sustained by a covenant with the pariah god, one that is continually renewed through the sacrifice of the spirit-souls of those who lose the Kólumejàlim (the Choosing of the Emperors).

Dhich’uné now believes he can reshape that covenant. Instead of the traditional sacrifice of defeated princes, he proposes to offer the spirit-soul of an emperor. He believes this will vastly strengthen the stabilizing influence of the One Other, making it eternal. He also believes that by becoming undead, he can survive the loss of his spirit-soul. Of course, no one can know whether this gambit will succeed, but Dhich’uné is convinced it will. He believes he has the knowledge and the will to deceive a pariah god into giving him what he desires.

Whether he’s right forms the central question of the campaign’s next (and likely final) phase.