SMOOSH JUICE

Levels Are For Video Games

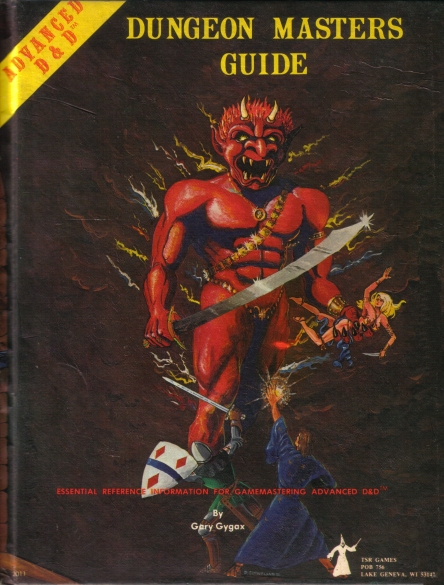

Today, “leveling up” is a central feature of countless video games, from sprawling open-world RPGs to mobile idle clickers. As anyone who reads this blog of course knows, levels come from Dungeons & Dragons, which introduced them half a century ago as a way to mark a character’s growth in power and ability through play over time. What began as a simple abstraction to track advancement has since become a core gameplay loop in video and computer games, where clear, incremental progress has come to be seen as essential to keeping players engaged.

As video games came to outshine the tabletop games from which they borrowed mechanical concepts like levels, it was perhaps inevitable that tabletop RPGs would return the compliment by inflecting their own designs with assumptions shaped by digital play. Over time, many adopted video game-inspired approaches to advancement: faster progression, more frequent rewards, and clearly defined “power-ups” that echo the dopamine loops of their digital descendants. The result is that some players now approach tabletop RPGs expecting the same steady drip of mechanical achievement they get from a screen, treating levels, feats, and skill boosts not as optional frameworks but as the very point of play. This feedback loop between mediums has reshaped how many people think about character advancement, often narrowing it to the accumulation of stats rather than the growth of an in-game persona, his relationships, or his impact on the wider setting. It’s also made me increasingly skeptical, if not outright critical, of levels themselves.

Before we get too far, let me be clear: this post isn’t an attack on levels. They’ve been a part of tabletop RPGs since 1974 and I’m not advocating for their abandonment. In the Gygaxo-Arnesonian conception of levels, a character can cast more spells, survive more wounds, and fight more fearsome foes as he advances. In this conception, levels bring a sense of scale and direction to campaigns and help frame a rough arc of a character’s growth after the fashion of, say, Conan’s rise from a young, inexperienced warrior to a battle-hardened general of Aquilonia (and, eventually, its king). It was, therefore, only natural that early computer RPGs, like Ultima and Wizardry would follow suit. Computers are excellent at tracking numbers, after all, and early video games needed straightforward mechanics.

As the years went by, the leveling paradigm took over. Players of video games came to expect a steady stream of mechanical rewards for their investment of time. Kill monsters, gain experience, level up. It’s a feedback loop as familiar and addictive as a slot machine and just as tightly engineered. With the massive success of MMORPGs and action-RPGs, the model has became entrenched and, unsurprisingly, it has filtered back into tabletop gaming. Many players now approach tabletop RPGs with the assumption that leveling up, or some equivalent form of mechanical advancement, is not only expected but essential.

And that brings back to something I’ve been feeling for some time: tabletop RPGs don’t need levels. In fact, they don’t need mechanical advancement at all.

Plenty of games, some of them quite old, have already demonstrated this. Consider my favorite roleplaying game, Traveller. Characters in Traveller begin the game with their skills already in place, having completed careers before adventuring begins. There is no leveling system. Characters can improve, albeit very slowly, with years of in-game training, but mechanical advancement is not central to the experience of playing Traveller. Instead, the game focuses on exploration, commerce, politics, and survival in an indifferent universe. What matters is what one’s character does within the setting, not how his numbers go up.

The same could even be said for a game like Call of Cthulhu, where the main arc of a character’s life isn’t defined by rising power but by gradual decline – into madness, death, or at best, retirement from delving into the Mythos. He might get better at Library Use or Spot Hidden, but he’ll never become an investigator resistant, never mind immune, to cosmic horror. That’s not the point of the game. Even RuneQuest, though it includes skill advancement through use, eschews levels entirely. A seasoned Gloranthan character is still vulnerable, still mortal. Advancement, when it comes, is more than a matter of increasing skill percentiles, but rather one of reputation, relationships, position within the world of the Third Age.

These games remind us that the real power of tabletop RPGs lies not in mechanics, but in meaning. Unlike a video game, which must quantify progress to function, a tabletop RPG has no such constraint. The game lives in conversation and imagination. If a Traveller character becomes the right hand man of the subector duke, or earns the ire of an Ine Givar terrorist cell, or uncovers the secrets of the Ancients, those are significant achievements. No hit points were gained, no XP awarded, yet the character has advanced in ways no level system can fully capture.

This is not to say that mechanical advancement is inherently bad, because I’ve used to good effect for decades. Leveling provides structure and creates a sense of forward motion. These are good things. For some players, it also scratches an itch that is very real. However, when mechanical growth becomes the primary – only – form of advancement, it distorts the nature of tabletop play. Players start to see everything through the lens of optimization. They choose actions based on what yields the most mechanical benefit, rather than what makes the most sense for their character or the world he inhabits.

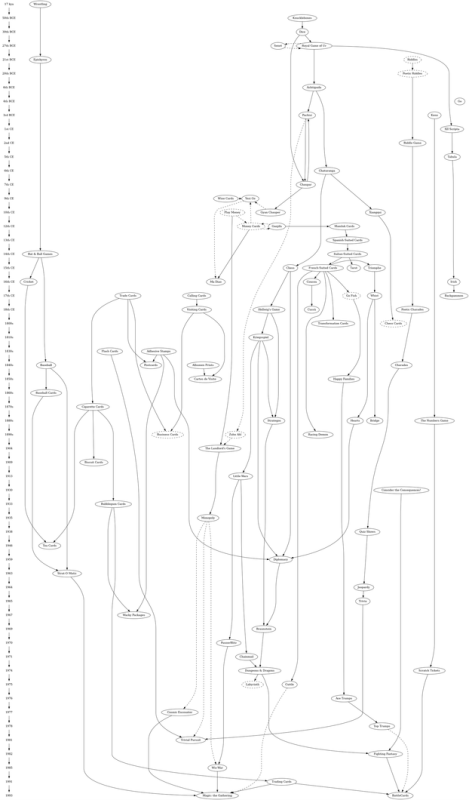

I’ve seen it happen; I suspect most of us have. A party bypasses an intriguing mystery because it offers no clear reward. A player makes choices like navigating a skill tree, optimizing for mechanical advantage rather than what fits the world or character. That mindset can make sense in a video game, where content is finite and progress must be explicitly marked. But tabletop RPGs aren’t software. They aren’t bound by code or limited to scripted outcomes. Their flexibility is their greatest strength. A character can change the world – or be changed by it – without his stats shifting at all.

If there’s one thing my House of Worms campaign has taught me, it’s to lean into that flexibility. We should reward clever thinking, bold risks, and engagement with the setting over mechanical upgrades. The most satisfying kind of advancement comes from caring about a character and his place in the world, not just from tallying experience points. When advancement does happen, it should feel earned not because the rules dictate it, but because something significant has happened.

Levels are great. Experience points can be fun. But they are tools, not goals. Tabletop RPGs aren’t about reaching 10th level. They’re about entering and exploring an imaginary world through an equally imaginary character. What matters isn’t how many hit points your fighter has, but what you do with them. Success might mean founding a colony, retiring in disgrace, making a terrible bargain with an otherworldly power, or changing the course of an empire. These are the kinds of outcomes that emerge from choices, consequences, and collaboration with the referee and other players, not from ticking boxes on a character sheet. Advancement in a tabletop RPG is ultimately about meaning, not math.

Those aren’t the kinds of achievements a level-up screen can show you and that’s exactly what makes them worth chasing – or, increasingly, it’s what keeps me playing after all these years.