SMOOSH JUICE

Precursors and Tangents to the Trading Card Game – Benign Brown Beast

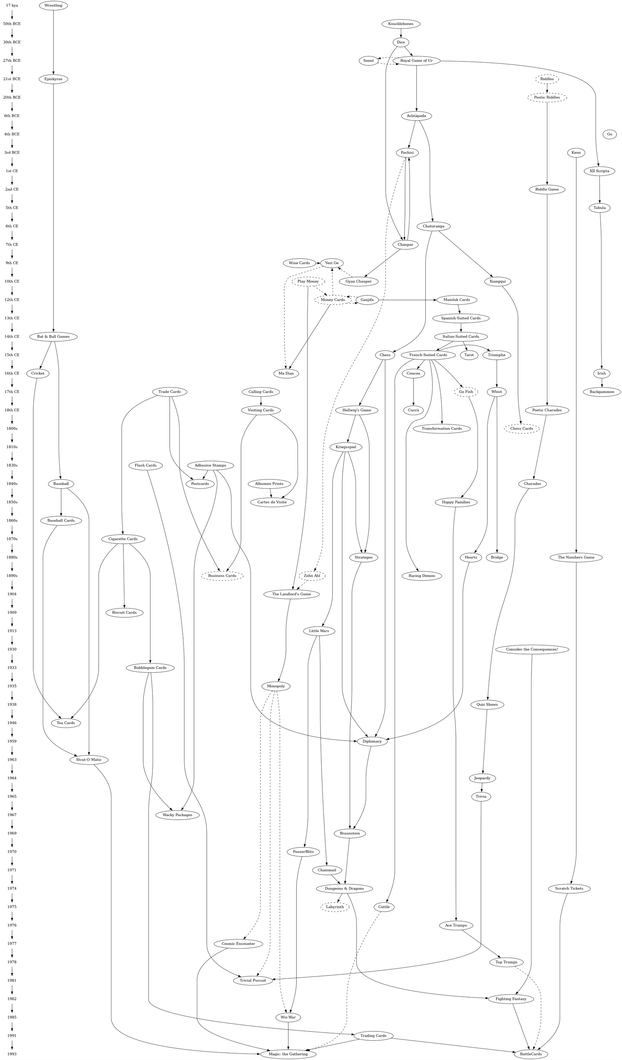

There are no novel insights here, but I needed to sort these things visually to get a handle on them.

Dashed arrows indicate a more inferential or a contested link, while solid lines are also pretty loose. Dashed outlines indicate that the placement on the timeline is unfixed or shouldn’t be taken literally.

Dashed arrows indicate a more inferential or a contested link, while solid lines are also pretty loose. Dashed outlines indicate that the placement on the timeline is unfixed or shouldn’t be taken literally.

I can’t describe this timeline easily in alt-text, but I can link the source files.

Notes

Wrestling

France, 17 thousand years ago.

Attested by cave drawings. The first evidence of a sport.

Knucklebones

Unclear, c. 5000 BCE.

Excavations uncover astragali or knucklebones disproportionately to other animal bones, suggesting some importance. Specific evidence of use in games and divination (either as tetrahedral dice or in the classic dexterity game) is not found until later.

Dice

Burnt City, Iran, 2800-2500 BCE.

Some of the first dice are found alongside either the royal game of Ur or the game of twenty. They’re actually pretty close to modern six-siders.

Senet

Egypt, c. 2620 BCE (Third Dynasty) or possibly older.

An ancient Egyptian board game with pawns moving on a grid. Before the invention of dice, it was played with “flat two-sided throwsticks.”

Royal Game of Ur

Iraq, early 3rd millennium BCE (Early Dynastic Period).

This game isn’t senet, but seems broadly similar. Many boards have senet on the reverse side, or a third game called “the game of twenty.” Again, it’s a racing game with a bunch of pawns moving along a path.

Riddles

Babylon.

The oldest recorded riddles are found in a school books. Their answers were not recorded.

Poetic Riddles

India, “second millennium” BCE.

The oldest riddle poems appear in the Rigveda, and are mystical in nature.

Episkyros

Greece, 21st century BCE (?).

Possibly the first “ball game,” although the ball is made of layered linen and sounds like it kind of sucks. Possibly the first “team sport.” It’s something in the rugby family.

Ashtāpada

India, 6th century BCE.

A game on an 8×8 grid, mentioned by the Buddha in a list of games that he would not play. The list also includes a 10×10 variant, and a variant played “in the sky” (believed to refer to a “blindfold” variant). It’s another race-type game, where players move their pawns in a spiral path around the grid and then make their way back to the edges. Movement is determined by the throwing of cowrie shells.

Go

China, 4th Century BCE (Eastern Zhou Dynasty)

Go appears more or less independently and doesn’t seem to directly influence much else. Still, it’s old and notable and interesting. Like the saying says, “chess was invented, go was discovered.” 1

Keno

China, 205-187 BCE (Han Dynasty).

A kind of lottery, possibly the first, where people bet on the random drawing of lots.

Pachisi

India, 3rd century BCE.

Described in the Mahabharata under the name “pasha.” Players race pawns about a distinctive cross-shaped board, moving according to thrown cowrie shells.

Ludus Duodecim Scriptorium

Rome, 2 CE.

AKA “XII Scripta” AKA “the game of twelve markings.”

Ovid mentions it in his Ars Amatoria. Used cube dice.

Riddle Game

Greece, c. 200 CE.

Riddle competitions are popular entertainment at symposia (drinking parties), according to Athenaeus of Naucratis.

Tabula

Constantinople, 480 CE (Eastern Roman Empire).

A game of tabula played by emperor Zeno is recorded, but there are claims that the game is much older.

Chaturanga

India, 6th century CE (Gupta Empire).

Progenitor of the chess family, played on the same 8×8 board as ashtāpada.

Chaupar

India, 7th century CE.

Possibly, the only distinguishing feature between chaupar and pachisi is the use of dice over cowrie shells. These are classically four-sided “stick” type dice.

Wine Cards

China, 9th century CE (Tang Dynasty).

A card-based drinking LARP. Everyone sits in a circle and takes turns drawing cards. Each card has a kind of role-play + drinking instruction on it. I believe this may be the first card game, regardless of later developments in e.g. standard packs of cards.

Yezi Ge

China, 9th century CE (Song Dynasty).

“The Leaf Game.” A confusing and debated game. It was probably similar to one of three things:

- A precursor to Ma Diao played with Money Cards. That would make this the first card game and firmly place money cards as the progenitor of modern playing cards.

- A complicated board game of promotion and demotion, similar to Gyan Chauper. In this case, “leaves” likely refers to the pages of a rulebook, and it would have used dice.

- A game using wine cards, in which case it may still be the first card game (but only in the sense that wine cards are already the first card game).

Paper Money

China.

Possibly a precursor to the play money that possibly preceded money cards. At any rate, a benchmark for printing technology.

Play Money

Unknown first appearance.

Money Cards

China.

Although not attested until later, it is suspected that Chinese money-suited cards may be the first standard deck of playing cards, perhaps evolving from the use of play money in gambling. Four suits of nine cards each.

Gyan Chauper

India, 10th century CE.

Basically Snakes & Ladders. Mentioned in a Jain holy text. As Senet may have started secularly and gained spiritual significance, so Gyan Chauper was intended to teach about karma.

Xiangqui

China, 10th century CE (Northern Song Dynasty).

“Chinese Chess.” Don’t remember how I arrived at the 10th century (Song Dynasty?) for this. Pieces move along the intersections instead of the spaces.

Ganjifa

Persia, 12th century CE.

Commonly circular. Four to eight suits of 10 pip cards and 2 court cards each.

Mamluk Cards

Egypt, 12th century CE.

The oldest surviving playing cards. Four suits of 10 pip cards and three court cards each, although the court cards show only abstract designs, possibly for religious reasons. This standard stays pretty constant from here.

Spanish-Suited Cards

Spain, 13th century CE.

Tens were removed from the Mamluk pack, possibly because 48 cards was easier to produce than 52 (printed on two whole sheets).

Italian-Suited Cards

Italy, 14th century CE.

Tarot

Northern Italy, 15th century CE.

Both a deck of cards and a trick-taking game. Four suits of 14 cards (10 pip and 4 court), plus 21 suit-less “trumps” and a suit-less and rank-less “fool.”

Chess

Europe.

French-Suited Cards

France, 15th century CE.

Four suits of ten pip cards and three court cards each. These catch on in part because the simplified suit designs are easy to print. They also divide the suits into two colors and have a queen (previous court cards were all male).

Go Fish

Unknown origin.

Triomphe

France or Spain, late 15th century CE.

So popular it displaced the game formerly known as trionfi, which in turn became tarocchi. A trick-taking game.

Ma Diao

China, 16th century CE.

A trick-taking game played with money cards. Because of its complexity at the time of first recording, it’s speculated that the game is much older, and therefore that money cards are much older, possibly predating ganjifa.

Coucou

France, 16th century CE.

A shedding game with single-card hands, sometimes using a stripped deck.

Irish

Scotland, 1507 CE.

A tables game, which is to say, played on a backgammon or tabula style board.

Trade Cards

France and England, 17th century CE.

Portable advertisements for a business (trade), with the intent of helping the potential customer remember and contact it. Before there were street addresses, for example, some of them had little maps on them!

Calling Cards

France and Italy, 17th century CE.

If you go your friend’s house and they’re not home, you can leave a note on a calling card for them. It’s decoratively printed on one side and blank on the other. Generally though, it doesn’t have contact info, since you were either already friends or important enough to know about.

Backgammon

England, 1635 CE.

Edmond Hoyle codified the strategy and rules of backgammon in 1753. The doubling cube was introduced in the 1920s.

Whist

England, 1674 CE.

A trick-taking card game. Edmund Hoyle similarly wrote the book on this one in 1742.

Bat & Ball Games

England, 18th century CE.

These all arise at once and are roughly indistinguishable: Rounders, Cricket, and Baseball.

Visiting Cards

Europe and US, 18th century CE.

The distinction here between “Calling Card” and “Visiting Card” is either fake or lost. But my inclusion of this additional evolutionary step is meant to indicate that the practice of exchanging them had both spread and codified into a complex etiquette.

Hellwig’s Game

Prussia, 1780 CE, Johann Christian Ludwig Hellwig.

Intended to both entertain and to teach about warfare. Based on chess, pieces move on a massive grid. But the grid squares can have different kinds of terrain on them and the types of piece include artillery, cavalry, and so on. Although he called it “kriegsspiel,” I have reserved that name for the later game by Georg Heinrich Rudolf Johann von Reisswitz.

Cuccù

Italy, 1717 CE.

Unsuited 38-card packs exclusively for playing a game like coucou. This is the oldest “dedicated deck” game, although other games were then developed for it. (Modern versions have 40 cards.)

Poetic Charades

France and England, 18th century (Regency Period).

A type of riddle where each syllable of the answer is given a separate clue, and furthermore where the collection of smaller riddles is in verse. (The example of a poetic riddle from the Rigveda is of this type.) Even though the form is quite old, they really took off in popularity around this time, in magazines and books, and possibly in social use.

Transformation Cards

France, Germany, and England, 1801 CE.

As playing card designs became more standardized, illustrators and artists began to superimpose humorous figures and scenes, “transforming” the cards. Some of these designs were never played (indeed some of them were literally unplayable, being printed in books), but that’s not the point. Throughout the whole history of cards, people have collected them for no other purpose than to admire, and this is just one last step on that path before we “invent” the collectible card proper.

Chess Cards

Southeast China, 19th century CE.

Two or four suits of 7 cards each (need after the seven chessmen in Xiangqui), possibly with some number of wild “gold” cards.

Kriegsspiel

Prussia, 1824 CE, Georg Heinrich Rudolf Johann von Reisswitz.

A wargame played on a grid-less, scale, topographical map using statistics compiled during the Napoleonic wars to more closely simulate outcomes. It introduced an umpire to maintain fog-of-war between the two players, and used hitpoints to track unit health. (It also used dice to modem the element of chance, although those were first introduced in an earlier intermediate wargame by Johann Ferdinand Opiz in 1806.)

In the 1870s, many credited Prussia’s victory in the Franco-Prussian war to their culture of wargaming.

Adhesive Stamps

UK, 1840 CE.

Innovations in adhesive technology allowed pre-paid “gummed” stamps and greatly streamlined the process of sending mail. The first stamp is the “penny black.”

Flash Cards

England, 1834 CE, Favell Lee Mortimer.

Designed for teaching phonics. Her other works are comically fearful and hateful to modern eyes.

Baseball

United States, 1845 CE.

“The Knickerbocker rules” laid out what is still the rough foundation of modern US baseball, although some recognizable similar rule sets predate them.

Postcards

United States, 1848 CE.

The first printed post cards are advertisements, and thus, trade cards (and were possibly considered as such). These evolve into picture postcards and eventually the well-known souvenir cards.

Albumen Prints

France, 1847 CE, Louis Désiré Blanquart-Evrard.

The first photographic process that both develops from a negative (allowing easy reproduction) and prints on a paper base (which is cheap).

Charades

England, early 19th century CE.

Acted, and eventually pantomimed charades became the dominant form, and are emblematic of the Victorian parlor game.

Happy Families

England, 1851 CE, John Jacques Jr..

A dedicated-deck game with art by Sir John Tenniel published for “The Great Exhibition.” Very similar to Go Fish, but all the cards are dealt out so there is no shared draw pile (“talon”).

The German quartets and American Authors are functionally identical but with different themes. In particular, German printers continue creating and selling quartets packs with new themes into the present.

Cartes de Visite

France, 1851 CE, Louis Dodero.

Miniature photographs reproduced from a negative. Despite the name, these weren’t used as visiting cards, but were instead swapped, mailed, collected, given, kept in albums, and admired.

Baseball Cards

US, 1860s CE.

The first baseball cards were trade cards intended to sell sporting goods and photographic cartes de visite from the teams themselves. But cigarette and other promotional cards would be the medium to carry baseball cards onwards.

Cigarette Cards

US, 1879 CE.

Initially inserted in packs of cigarettes to stiffen the packaging, they may have started as advertisements, but manufacturers quickly started adding art and text to increase appeal. These could be about anything: sports, history, trains, nature, pretty women, etc. There is a contention that these are still “trade cards” because they could still serve as advertisement, but I would argue that they should instead be considered as promotional items or prizes.

Strategos

US, 1880 CE, Charles A. L. Totten.

Two related games, one played on a board and one on three maps with fog-of-war and a referee. Because it defers to the referee when rules are unclear, considered part of the “free” kriegsspiel movement.

Hearts

US, 1882 CE.

An inverted trick-taking game, where tricks are to be avoided.

The Numbers Game

Chicago, US, 1885 CE.

The classic lottery set-up: pay money for a ticket with a number and if your number comes up from a random source, get a portion of everyone’s ticket sales back.

Bridge

England (?), 1886 CE.

AKA “biritch” AKA Russian Whist.

Zohn Ahl

Kiowa Territory (Oklahoma), US, 1898 CE.

Stewart Culin records the rules of this game in his book, Chess and Playing Cards. Two-sided sticks are thrown “vigorously” against a flat stone, and then read to determine how two awls race around a circular board.

It’s unclear how old the game may actually be (certainly it’s older than 1898), and whether it shares a history with other similar games or is an independent invention. However, the rules in the book itself are suspected to have been part inspiration for The Landlord’s Game.

Racing Demon

England, 1890s.

AKA “Nerts.” A kind of competitive solitaire, which I think is notable here for raising each player to bring a separate (albeit identical) deck. This pattern shows up later in the trading card game, largely because players want to keep the cards they start with.

Business Cards

Unknown, c. 1890s CE (suggested by Google n-gram).

Trade cards and visiting cards are both subsumed into business cards. While a visiting card has no contact info, a business card does. While a trade card advertises a business in general, a business card only represents an individual within an organization. There could be something here about the folding of personal identity into corporate.

The Landlord’s Game

Delaware, US, 1904 CE, Elizabeth Magie.

Direct precursor to Monopoly and many other board games, intended to demonstrate the iniquity of private land ownership. It adds cards to dice, play money, pawns, and a board.2

Biscuit cards

US, 1909 CE.

Bakeries begin including baseball cards in their biscuit packaging. This practice continues today in Japan with collectible anime-themed “wafer cards,” although I couldn’t find out much more.

Little Wars

England, 1913 CE, H.G. Wells.

A book of rules for miniature wargaming with toy soldiers. Artillery fire was simulated by spring-loaded cannons, and there were no other randomizers. Perhaps because of the material (and enthusiasm) shortages of WWI, it didn’t really catch on.

Consider the Consequences!

US, 1930 CE, Doris Webster and Mary Alden Hopkins.

The earliest known gamebook, a romance.

Bubblegum Cards

Boston, US, 1933 CE.

Like cigarette cards, but for kids! After WWII, cigarette cards didn’t make a comeback, but bubblegum cards (in the US) and tea cards (in England) filled the niche. Again, mostly baseball cards.

Monopoly

US, 1935 CE.

Charles Darrow sold The Landlord’s Game to Parker Brothers as his own and it becomes wildly popular. This version strips out the Georgist messaging, leaving only the random rags-to-riches slog of a game we all know today.

Quiz Shows

US and UK, 1938 CE.

Spelling Bee in the UK is the first television quiz show. Information Please in the US is the first radio quiz show. The comedic, disarming, and possibly embarrassing nature of the format mirrors Victorian parlor games.

Tea Cards

England, 1946 CE.

Like bubblegum cards, but English. Mostly cricketers, if I understand.

Diplomacy

US, 1959 CE.

A sealed move “war game,” except the most of the conflict is political instead of military. There is no randomization or differentiation in a military encounter.

Strat-O-Matic Baseball

United States, 1963 CE.

Strat-O-Matic Baseball is, kind of, a game played with baseball cards. You could even collect and trade the cards, although they are sold as a set. But the real complaint I have with it is that the cards are ugly. They’re really only lovable as a game piece.

Jeopardy!

United States, 1964 CE.

Perhaps the most famous of quiz shows, employing an “inverted” answer-first format. Approval faced an uphill battle, after the 1950s quiz show scandals.

Trivia

United States, 1965 CE.

In the 1910s, people had begun publishing books of “trivia,” but the term was not used for an informal parlor game of swapping pop-culture questions and answers until the 1960s. The first written reference to an organized “trivia” competition is not until 1965, at Columbia University.

Wacky Packages

United States, 1967 CE.

Adhesive-backed trading cards with parodies of popular brand logos by a slew of notable artists. From 1973-75, Wacky Packages out-sold baseball cards. Obligatorily sold with a stick of gum.

Braunstein

Twin Cities, US, 1969 CE, David Wesely & Dave Arneson.

David Wesely attempts an experimental wargame where each player represents only one individual involved in the conflict. Players much preferred role-playing and exploring to wargaming, and he would have called it a failure but they all wanted to do it again. Dave Arneson took over the running after David Wesely began serving in the army.

PanzerBlitz

Baltimore, US, 1970 CE.

A tactical board game from Avalon Hill. Among other innovations, it introduced “geomorphic” map tiles, which due to a misunderstanding has become the standard term for any reconfigurable game board.

Chainmail

Lake Geneva WI, US, 1971 CE, Gary Gygax & Jeff Perren.

A medieval miniatures wargame, including an appendix with rules for playing magical creatures and scenarios from the popular fantasy of the day.

Scratch Tickets

Massachusetts, US, 1974 CE.

A thin layer of latex obscures a printed number, the numbers either win or lose. This relocates the “excitement” of gambling from a shared, paced drawing of numbers (or other determination of an event, like a race) to a personal quick fix available whenever.

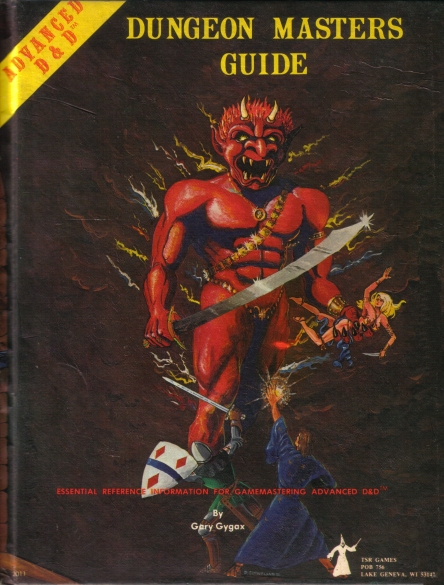

Dungeons & Dragons

Lake Geneva WI, US, 1974 CE, Gary Gygax & Dave Arneson.

etc.

Cuttle

US, 1975 CE at the latest.

A “combat” type card game with many similarities to Magic: the Gathering. It is unknown if Richard Garfield was familiar with it.

Labyrinth

USSR, 1970s.

A pen-and-paper dungeon-crawling game. English-language sources are thin on the ground. While it bears some resemblance to Wiz-War, I’m hesitant to draw a line across the iron certain.

Ace Trumps

Germany, 1976 CE.

A twist on the classical Quartets (Happy Families), where cards must be “won” by comparing various dimensions and details printed on the cards. In theory, this is educational, as say, if the theme of the pack is “cars,” you’d end up leaning facts about all those cars over time.

Cosmic Encounter

US, 1977 CE.

A sprawling expandable sci-fi board game with complex cards that can completely upend the “rules” of the game.

Top Trumps

UK, 1978 CE.

At some point the collection/families aspect is dropped from the game, and I’m unsure if that was in 1978 with Top Trumps or in 1976 with Ace Trumps.

Trivial Pursuit

Niagara on the Lake Ontario, Canada, 1981 CE.

Fighting Fantasy

UK, 1982 CE, Steve Jackson (British) & Ian Livingstone.

The Warlock of Firetop Mountain is the first gamebook in the series. A version of the system used in these books eventually goes on to become Troika!

Wiz-War

US, 1985 CE.

A “beer and pretzels” dungeon-crawling board game with a reconfigurable labyrinth and complex effect cards.

Trading Card Packs

US, 1991 CE.

We’ve had “trading cards” since we’ve had cards, but until now they were also always something else: business cards, playing cards, bubblegum cards, etc. In 1991, they took the bubblegum out of the packs and you could finally just buy randomized cards for the pure unalloyed reason of collecting them.

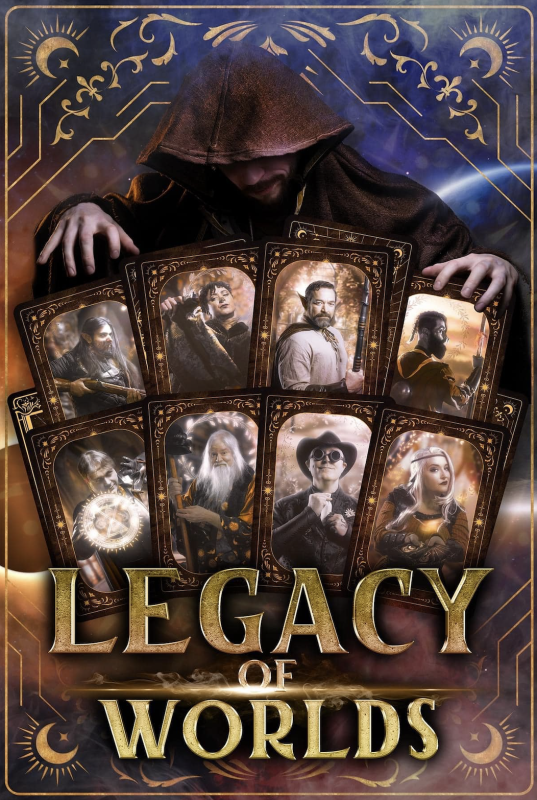

Magic: the Gathering

US, 1996 CE, Richard Garfield.

Richard Garfield’s greatest game for now, commonly considered the first trading card game and certainly the best known and most successful.

BattleCards

US & UK, 1996 CE, Steve Jackson (British).

Debuted at exactly the same GenCon as Magic. For a variety of reasons, it didn’t catch on, but I don’t think “not being as good as Magic” is a good reason to deny it the equal title of “first.” It’s certainly weird enough to learn from.

Thoughts

- We may never know the first of something. Archaeology is hard, and I’m not even an archaeologist. Also, everyone wants to be the first, to say the one they found is special, so the farther back you go, the more tenuous the claims get.

- It’s not really important who did something first if it gets reinvented later. For example, suppose that Zohn Ahl is an independent creation of the Kiowa people. Does it matter then that it shares many similarities with Pachisi? Or does it matter3 more that it was in a book read by Lizzy Magie?

- Technology drives innovation. Papermaking allows cards. Adhesives allow postage which allows postcards. Pens allow pen-and-paper games. Broadcasting allows shared pop-culture which in turn allows trivia. Etc.

- Games are iterative. Chaturanga uses an Ashtāpada board, Wiz-War uses tiles like PanzerBlitz.

- People like to collect and trade little objects, and cards are a perfect example. Cards are human: designed to fit in our hands and pockets; to be shared, exchanged, and collected; and to reflect our culture.

- Games touch all areas of humanity: religion, warfare, sport, drugs, food, money, gambling, etc.

Disclaimer

This thing is a bit of a mess. Fact-check anything you plan to use seriously.

Bibliography

There’s a lot of Wikipedia and Board Game Geek in this one, but also:

- The Chinese “Leaf” Game surveyed by David Parlett.

- Board to Page to Board by Philip M. Winkelman.

- Get Rich Quick: The American Lottery by Rund Abdelfatah et al.

- Pagat Card Game Rules

- World of Playing Cards

- The History of Playing Cards, the Maniculum Podcast.

-

Which may do a disservice to the many historical and regional variants of the game, but it’s a fun thought.↩︎

-

To be sure, I am not claiming it is the first game to do this.↩︎

-

“Matter” of course in a progress-focused historical sense. To the Kiowa people, it matters only that they’re playing it, that they’re learning, having fun, and all the other reasons a game might “matter.”↩︎