SMOOSH JUICE

Serious Fun: An Ode to GDW’s RPGs

As I’ve said innumerable times since I started this blog, I was never a wargamer.

I didn’t have shelves stocked with hex maps or spend my weekends calculating armor penetration on the Eastern Front. I wasn’t part of that sacred brotherhood that spoke in acronyms and argued over the effective range of a Panther’s 75mm gun. Yet somehow, whether by accident or by fate, I fell in love with a company born from that world: Game Designers’ Workshop, better known as GDW.

GDW got its start in 1973 as a publisher of serious, detail-oriented, historical wargames. While I didn’t know almost any of this when I first encountered their roleplaying games, I nevertheless felt it. Even as a teenager, I could tell there was something different about the games GDW made. Where TSR gave us magic missiles and gelatinous cubes, GDW gave us vector movement, speculative trade tables, and the quiet horror of running out of fuel in central Poland.

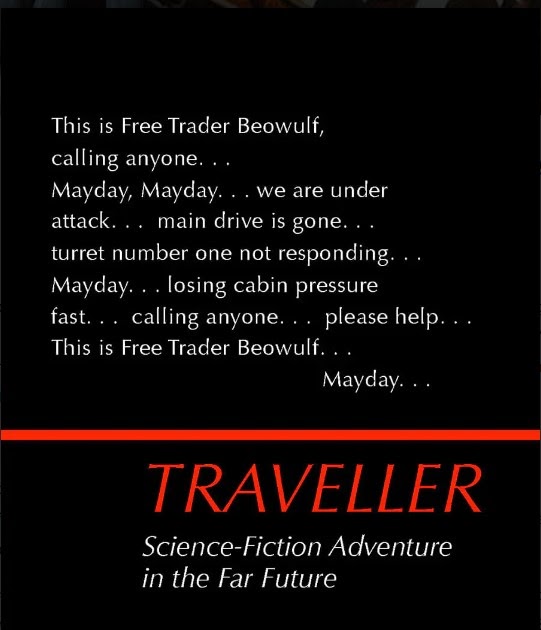

Like a lot of roleplayers, Traveller was the game that first introduced me to GDW. I came across it several years after playing Dungeons & Dragons, and the contrast was immediate. Traveller didn’t just offer you a character; it offered you a life. Character generation gave you a person with a backstory in the form of a career and an odd collection of skills and equipment. Of course, if your rolls were unlucky, all you got was an early grave before the campaign even began. This was the kind of game where you might end up as a grizzled ex-Merchant with a gambling habit and no pension instead of a mighty-thewed barbarian.

Traveller’s vision of the far future wasn’t shiny or triumphant. It was bureaucratic, complicated, and often rather gray. There was something fascinating about how it treated space travel not as an exciting novelty but as a job, equal parts dangerous, expensive, and frequently boring. It was, I later realized, a very wargamer approach to science fiction: not about wish fulfillment, but about systems, trade-offs, and consequences. Even though I’d never played Drang Nach Osten! or Pearl Harbor, I could still intuit that GDW’s RPGs were built by people who thought about conflict, logistics, and uncertainty in a fundamentally different way.

That sensibility was especially evident in Twilight: 2000. T2K was a game that asked, “What if the Cold War ended in fire and now you’re out of gas in a broken-down Humvee, trying to negotiate with a Polish farmer for potatoes?” It was bleak, but it was real. Every decision mattered. Ammo wasn’t just an abstraction; it was the difference between life and death. Characters had to eat, find shelter, manage morale. There were no magical solutions, just the grim satisfaction of surviving one more day.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but I think Twilight: 2000 taught me something about roleplaying that’s stuck with me to this day: adventure doesn’t have to come from epic quests. Sometimes, it comes from the struggle to get by in the face of all sorts of obstacles, both big and small. Fixing a broken axle under sniper fire, bartering for antibiotics with a suspicious local, or just figuring out where the next meal is coming from. That was the adventure.

Later, I picked up Traveller: 2300 (later rebranded 2300 AD), which built on the ashes of Twilight: 2000’s world to envision a future shaped not by utopian ideals, but by historical inertia. Nations rebuilt and space was colonized by corporations and governments with agendas rather than by high-minded dreamers. It wasn’t heroic, but it was plausible. It had an internal consistency that made it feel like a real place, even if that place was cold, indifferent, and occasionally French.

Then there was Space: 1889, GDW’s pioneering foray into what we’d now call “steampunk,” complete with ether flyers, Martians, and an entire solar system shaped by European colonialism. Space: 1889 had a slightly lighter tone than its siblings, but it nevertheless bore the hallmark GDW seriousness. There was surprisingly detailed setting material, a respect for history, and a commitment to internal consistency that made its outlandish premise feel oddly plausible. Even in a world where Queen Victoria reigns over Venusian swamps, GDW still asked you to think like a colonial officer, an inventor, or an explorer navigating the realpolitik of empire.

Finally, there was Dark Conspiracy, a game that asked what would happen if you took the economic anxiety of the late ’80s, mixed in extra-dimensional horror, and then handed the whole mess to a security contractor. As I mentioned in my recent Retrospective, Dark Conspiracy failed to live up to its full potential, but even so, it was strangely compelling. Beneath the neon-soaked dystopia and monstrous invaders, you could still feel GDW’s trademark seriousness at work: the emphasis on gear, tactics, and systems that made survival feel earned rather than assumed.

What bound all these games together wasn’t genre; it was approach. GDW brought a wargamer’s eye to RPGs. They cared about detail, about systems that worked even when they weren’t elegant (though I continue to maintain that Traveller is one of the most mechanically elegant roleplaying games ever designed). GDW wasn’t afraid to make things difficult or even bleak, because they believed that challenge and immersion went hand in hand. As a player and a referee, I must confess that I didn’t always understand every rule. I sometimes made do with what I thought they meant, but I nevertheless respected the intent. GDW’s RPGs weren’t about wish fulfillment. They assumed you were already smart enough to navigate their worlds and tough enough to handle the consequences.

As someone who entered the hobby on the more fantastical side represented by D&D and Gamma World, that was both refreshing and bracing. GDW showed me that roleplaying could be serious, by which I don’t mean dour, but serious in the best possible way. Roleplaying games could provoke you to think, to plan, and to inhabit a world that didn’t care about your character sheet unless you used it wisely.

So, as I said at the beginning of this post, I was never a wargamer, but I was – and remain – a GDW fanboy. Their RPGs showed me a different way to play, a way shaped by history, consequence, and thought. Almost thirty years after the demise of the company, that kind of grounded imagination still feels like something worth celebrating, hence today’s ode to the amazing roleplaying games of Game Designers’ Workshop. What an incredible company, what an incredible library of games.