SMOOSH JUICE

Designer Diary: Gun It | BoardGameGeek News

The car races down the road. Words are spoken amongst the crew. Equipment changes hands — then time runs out and the Inertia Corporation is on top of you. You think you know what’s about to happen…

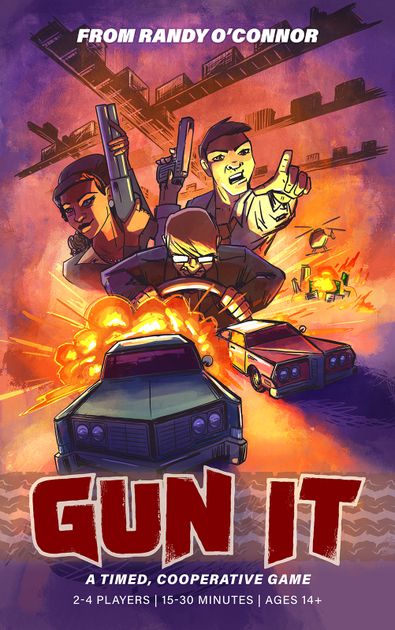

Hi, folks! I’m Randy O’Connor, independent game designer and publisher, and creator of Gun It, an action movie on your table for 1-4 players. In this designer diary, I want to run through the tenets I learned to create a highly thematic board game.

What Is Gun It?

Gun It puts you inside one vehicle in the middle of a shootout against the Inertia Corporation. Inspired by thrilling car sequences in films like Ronin, Heat, The Matrix Reloaded, Bullitt, Mad Max, and so many more, you have loaded weapons and must fight off a mega corporation that is trying to stop you.

Whether it’s Doyle in The French Connection, Neo in The Matrix, or McCauley in Heat, the beating heart of those action movies is the anticipation of what’s about to happen — seeing the shotgun tossed over, loaded, and cocked…but with the trigger yet to be pulled.

I’ve always loved the idea of being in the backseat of a car in an action scene. Trying to capture this experience was one of my first three board game ideas, and it took years simmering in the back of my head, along with a few rough sketches in notebooks, before I landed on the seed of what I have now.

To bring that fantasy to life involved drilling a bit deeper into the exact moment I wanted to capture:

• Who are the players?

• What are the game pieces?

• What is “the moment”?

At the Table

I design video games by day, and I’m drawn to tabletop games for the social component. If I’m at a table playing a game, I want to interact with people. An early revelation I had was how immediately a rectangular table with four players can feel like being seated in a car. Choose a driver, and you can see the other seats neatly fall into place.

First tenet of a thematic game: I avoided naming the player characters. You are not Mr. Pink, Jackie Brown, or any other made-up name. It’s you in that car.

A game can use different ways to tell you who you are: It can ignore any aspect of roleplaying; it can give players imaginary names and portraits in the text; or it can talk to the players, putting them in the situation directly. I find the latter approach to be the most compelling. I want you to see yourself in that seat. Sometimes I name avatars, as in my previous game Roll In One, but I like connecting our games to the world around us more than I want to imagine a world apart. It can be less comfortable to say it’s me, myself, and I in the game, but I find that tension more meaningful.

Just by sitting and picturing ourselves in the car, we’re 30% of the way to Gun It.

Second tenet: Game actions and pieces should be analogous to actual concepts and in-world objects. The more abstract the game piece or system, the more your theme disappears.

A game can capture only a minuscule portion of an actual thing. There are infinite angles from which to view a car chase. You could model the car rapidly getting damaged by each swerve and impact, and seek to keep it from jumping too many curbs. You could explore the motivations of those who hired the henchmen giving chase. You could be a city manager dealing with the aftermath dealt to the city and its citizens.

To me, the art of game design is figuring out which angles, concepts, and boundaries to put in the box for this particular experience. I may start and explore lots of ideas, but each feature will reinforce or distract from the specific emotional beat, and I want only what makes sense.

We Do Not Need Much to Tell a Story

There’s a crew car tile. Place it on the table and rotate it to the same orientation that everyone’s seat dictates. Surround the car with vehicle tiles from the evil Inertia Corporation. These vehicles have health and may have orange arrows pointing toward other tiles.

For the crew, randomly hand out three cards to each player: Everyone gets an arrow, a number, and a piece of equipment, most likely a gun. Each crewmember’s three cards add up to one action: what they’re doing, where that action is directed, and when it happens. For example:

The final piece of the game is that if your gun does enough damage to take out a vehicle, the flaming wreckage may cause collateral damage, which could destroy another hostile…or that damage could be pointed at you. Each vehicle shows clearly with orange arrows what it will damage when you wreck it.

There are additional game elements I don’t talk about in this post, such as settings and scenarios, but even more features were culled because they were unrelated to “the moment”: people in a car who are planning the ten seconds of action about to happen. There had been larger strategic elements — features like accuracy, personal motivations, more complicated point systems — but I tried to always remember the feeling of those people in the car.

The second of three layers is complete: We have the scene, and we’ve all got our actions.

“Here, Take the Shotgun” — Tension and Choice

Look at the table, everyone has their cards out. Players may exchange any of the three cards they are holding. Swap arrow cards to point your gun another direction, or number cards to take your action after your crewmate instead of before, or maybe swap guns, or switch who is holding the wheel if the driver has the best shot.

You can see everything that’s going to happen if you have the time…but you don’t. You’re in an action scene, so Gun It is a timed game.

Tension comes not only from the time pressure, but from twelve core cards split amongst the players: four cardinal directions — forward, back, left and right; the numbers one through four; and four core equipment cards: steering wheel, pistol, shotgun, and uzi.

Only one player can act forward, only one to the left, to the right, toward the back. Only one person gets the shotgun, or the wheel, or the pistol. This is your challenge.

The primary tenet of my design philosophy: Be straightforward and build the game around the action or moment you like the most, but give your players good reasons to act counter to what they’d like to do.

From day one, Gun It‘s design has centered on someone getting to say, “Give ME the shotgun!”

But to make it interesting, that same player must have cause to say the inverse: “Hey, YOU, take the shotgun.”

The game must challenge the fun choice. Maybe the shotgun is too much power for what you’re trying to do right now; maybe your crewmate has a better line on a hostile vehicle; or maybe you’ll shoot your crewmate if you hold onto the shotgun.

Who holds the pistol, and who holds the shotgun? Who is aiming forward, and who is aiming back? As you improve, you will discover how much you can pull off with such a limited set of cards.

In Brian Upton’s great book The Aesthetic of Play, he explores how a game can be tense whether or not you’re doing anything in a particular moment. It’s the anticipation. It’s exciting to anticipate a few moves ahead. If a player can anticipate only the next few seconds and no further, the game is confusing. If a player can anticipate the next thirty minutes, the game gets boring.

Your first choice will influence the next, and always the game is bringing you back to that moment of discussion over who has what and why. You’re trying to figure out how to knock down the dominoes without knocking yourself down, but you aren’t really sure, and time is ticking. Is that helicopter going to be in the right spot? There’s an intersection ahead. You might suddenly scramble as you realize you’re missing an opportunity. “Give me the pistol, take the shotgun! If you change order with Pam, we can bring the chopper down!”

Thanks for reading, and I hope you found this interesting!

Randy O’Connor

Randy O Games

/pic7504699.jpg)

/pic8633848.png)

/pic8327770.jpg)

/pic8340682.jpg)

/pic8340681.jpg)

/pic8327769.jpg)