SMOOSH JUICE

Designer Diary: 23 Knives | BoardGameGeek News

by T. Brown

Intro

In the summer of 2007, I was living in Rome on a study abroad program, taking history classes, and spending my free time getting lost among ancient ruins, historic basilicas, and labyrinthine streets.

I came to Rome with the notion of becoming a writer, idolizing the poet John Keats on his deathbed overlooking the Spanish Steps and Bernini’s Barcaccia. The romantic allure of Rome — its history, its lifestyle, and its passions — influenced everything in my life. It was there, studying history, that the title 23 Knives burrowed itself into my brain, even though I had no idea it would turn out to be a board game.

A few years later, I entered a master’s program in my home state of Wyoming, and I started to get invited to game nights at the university. My friends were playing Catan, Betrayal at the House on the Hill, and Through the Desert. Apart from a lot of Risk and traditional card games and roll-and-move type board games (which I had loved when I was younger), my passion for board games was limited, so these modern board games were a revelation.

Academia and writing was tiresome by the time I graduated, but gaming reinvigorated my creativity. Gaming was mental and intricate and filled with meaning, just like writing. The understanding and guidelines that the structures of games provided also gave me a great amount of solace when I needed it.

In games, you know the rules and the limits of what can and can’t happen, whereas life can get complicated and change quickly. It was with this in mind that I started focusing on creating board games as a kind of practice or exercise to deal with the things I couldn’t control. I had fiddled with a few games trying to map or work through inner issues — pretty much tantamount to writing poetry as a teenager: It made me feel better, but no one should ever read it.

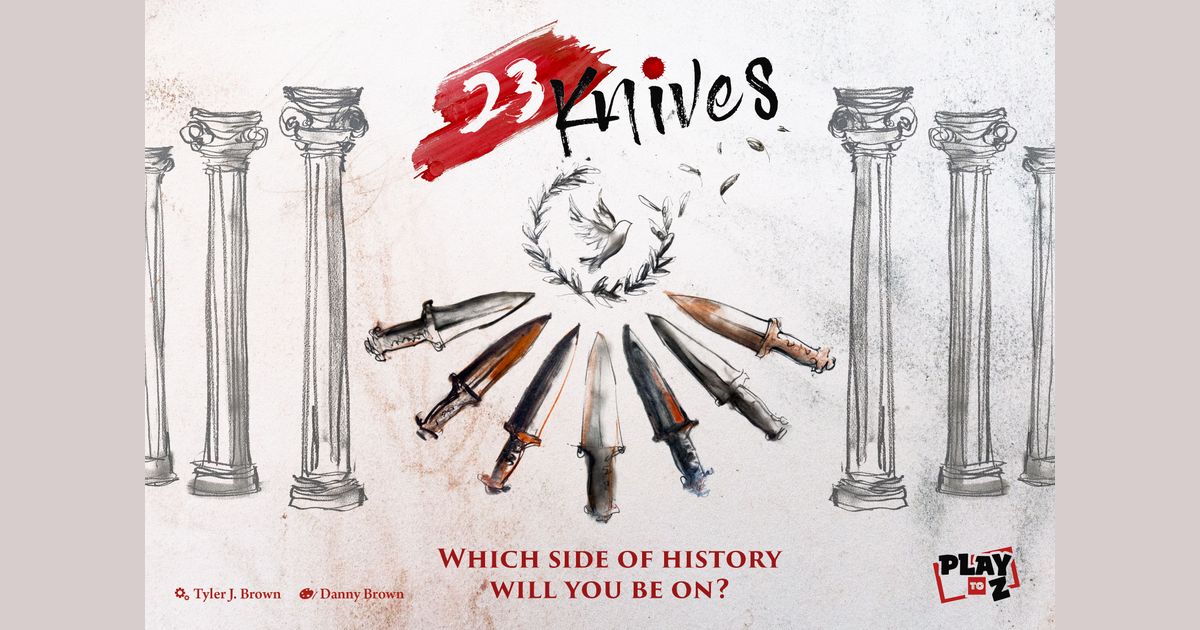

My first attempt at making a game that I thought other people would enjoy started in 2018. The theme was easy: ancient Rome, because who doesn’t like ancient Rome? And I already had the title: 23 Knives.

I was playing a lot of social deduction games at the time, which seemed like a promising foundation. I decided the game needed to end with Caesar living or dying, and his fate had to depend on whether there were more or fewer than 23 knives. The next step was how to make it into a game and discover what kind of game it would be.

First Lessons

23 Knives started as a simple social deduction concept. Some players would have the objective of murdering Caesar, and others would attempt to save him. Throughout the game, they would have to deduce who was and wasn’t on their side, while placing knives or warnings into the Campus Martius in order to kill or save Caesar.

My first attempt at social deduction failed. I focused on the social aspect, encouraging table talk, thinking that this was the most important aspect of social deduction.

It’s not.

This early iteration of the game allowed players to move to different locations and resolve effects that would eventually allow them to secretly place knives into the Campus. This worked on a mechanical level; players were getting cards and playing them into the Campus, and they were doing what I had intended: trying to save or kill Caesar — but when players moved to locations and placed cards into the Campus, no one knew what anyone else was doing. It was all very secret. My friends were not impressed.

My first lesson: In order for deduction to work, information must be revealed.

When I reflected on this, I realized that I had created a guessing game. It wasn’t fun, but I was learning…

In my next iteration of 23 Knives, I replicated some of the mechanisms in The Resistance. The Campus triggered once a number of cards were present. The cards were shuffled, then revealed, which allowed players to deduce who played the knives and who played the warnings. This still felt wrong — not sure why exactly, but I didn’t like it, and it felt disingenuous.

I find that most social deduction games end with almost everyone knowing who is who, which leads to a dull endgame experience. I wanted to create a more climactic and memorable endgame. I wanted all the cards to be revealed one-by-one as a final tense surprise. I didn’t want to slowly reveal cards throughout the game, so I decided instead to rely on the locations to help reveal information about players’ intentions.

Originally, locations allowed players to gain cards and affect other players. (Spoiler alert: They still do.) The locations were variable, though, and set up randomly each game in a circle around a public area. Players moved clockwise to new locations, and each time they moved, they had to discard a card to the public for each step they took. Thematically, the more players moved around Rome to take actions, the more they had to reveal about themselves by which cards they discarded.

Functionally, the locations haven’t changed much since that first iteration, but I had a playtest at BGG.Spring in Dallas where a playtester asked me, “Why are the locations variable for each game?” I didn’t have a good answer; more importantly, I didn’t really care, so I knew it needed to be removed. I had to wake up to the fact that intentionality should be in every moment of a game (lesson #2).

I started to focus on making the locations distinct and meaningful, and since I realized that variability doesn’t create replayability and that giving players five different ways to do the same things was a bad design decision, I made the locations static and allowed players to move around them however they wanted, which allowed players more meaningful choices.

While I was at it, I dug deeper into the thematic elements of the locations and nailed down what would fit better for Rome: The Campus Martius became the Theatrum di Pompeii, and then more specifically, into the final Curia di Pompeo as I did more research; the Public was folded into the Tiber River, Caesar Domus was scrapped entirely in exchange for the Temple (which I’ll talk more about later).

Now that I had worked out how I needed to create an intentional experience and uncluttered the idea of social deduction, the game slowly revealed itself to me. I didn’t want it to be the same as other social deduction games. I always hated the hope of being dealt an exciting role, then getting one I thought was boring, which led to a game I was less invested in. Essentially — and I don’t think I am alone here — I hated being a villager when I was so excited with the possibility of being a werewolf, or a hunter, or a smattering of unique characters. I wanted a choice. To work around that, I chose to make the design more about manipulation and less about deduction, and I did this by using sway cards.

One of the big differences between 23 Knives and comparable games like Secret Hitler, Blood on the Clocktower, etc. is that your allegiance can — and most likely will — change. If you start as a Nazi in Secret Hitler, you remain a Nazi, and your responsibility is to make sure fascist policies pass or Hitler becomes Chancellor. In 23 Knives, you may start as a Loyalist wanting to save Caesar, but throughout the game you can affect your own allegiance and work toward becoming a Liberator, while at the same time manipulating others’ allegiances.

Each citizen begins with a specific allegiance: You want to kill or save Caesar — or a neutral, in-between role, but this option didn’t exist until later in the design when I realized what it obviously should be. The range of each citizen’s allegiance starts between one and three and is indicated by how many blood drops or laurels are present on the card. If you have two laurels, then you are essentially a value two Loyalist to Caesar; if you have three blood drops, you are a value three Liberator.

Throughout the game, this allegiance changes and shifts. Other players can place sway cards in your tableau that depict one or two laurels or blood drops, and these icons combine with the laurels and blood drops on your citizen card, with each laurel and blood drop counting against each other. You may not know exactly which side each player is on, but you can certainly try to manipulate them one way or the other. The only game I could think of that had similar aspects to this was Dȗhr: The Lesser Houses, so I knew I was on the right track to create something unique (though later I learned about Homeland, which has a similar mechanism as well).

Originally, the game ended with either the Liberator or Loyalist team winning. All players on the team would win. It was a fine conclusion, but I didn’t love it. In ancient Rome during the conspiracy, nobody was safe. Caesar’s closest friends turned on him. Nearly everyone was self-obsessed and selfish. I wanted to recreate that around the table. I wanted players to look at their teammates and think, “I know you want to kill Caesar, but I also want to kill him AND I want to win.” This added a layer to the game that captures the mood of the conspiracy, as well as the paranoia. Early on, I changed the victory condition so that only the player most dedicated to killing or saving Caesar would win. In case this isn’t clear, that means you would try to sway others to your side, but at the same time keep those “teammates” at a distance — then sway them toward the opposite side so that only you would win.

A Small Aside on Aesthetics and Discouragement

At this point in the design (probably much too early), I decided I needed to have real art and real cards. There’s definitely a few lessons to be learned here, but the one that sticks with me the most is that for a designer who obsesses over aesthetics, sticker paper is wonderful. Even bad art taken from Google that’s thrown together, printed on sticker paper, and stuck to the backs of old Magic cards or cardboard looks much nicer than hand-drawn bits and helps players visualize the story you’re trying to tell. This is the game design version of the old writing adage “Show, don’t tell”.

So many designers rail against spending time making prototypes pretty, but plain white cards stickered with decent art will get much more attention at prototyping events and game nights and help bring the game to life. I also recommend this much more than drawing two hundred mini knives, doves, blood spots, and laurels…

This leads to my next point in this aside: burnout and discouragement.

Living in Wyoming, I have a tough time finding people to play games with — and even fewer people who are willing to play prototypes. I have a great game group and bless them for playing my prototypes as much as they do, but the small population and tiny gaming community can be tough.

I deal with this discouragement by making things pretty. I find it a similar, but different creative outlet than game design, so when I am depressed and think my games will never get played or I am unable to find playtesters (or simply too anxious to ask), I distract myself and take a bit of pride in making them more presentable for the moments they actually get seen and played.

Not sure if anyone needs to hear this, but there it is: If you get discouraged, finding a parallel way to work on a design you’re sad about is a great way to work through those slumps and help reignite some of the initial excitement.

Theme and Control

Okay, back to the design.

You might be wondering: If you can manipulate others, how well can players control their own citizen’s allegiances? Well, control was and is a particularly tough problem…but I approached it in three ways.

First, the citizens in the game were real people. They lived through this point in history, they walked the streets of Rome, they touched the marble columns that form the foundations of the monuments that still stand today.

Ancient sources list sixty or so conspirators. I started with eight — mostly the ones Shakespeare used to prop up his history — but there needed to be more and they needed to be special; they needed to represent who these people were historically. I wanted the history to really hit people in the face, I wanted it to come alive, because, this is — after all — a historical game.

Each citizen begins with an allegiance that, as closely as I could discover, matches their opinion toward Caesar in 44 BCE. Marc Antony loved Caesar and would follow him anywhere, so he starts with three laurels. Decimus Brutus, one of Caesar’s closest friends, begins the game with two laurels. Historically, Decimus led Caesar to his death and was one of the five to stab him during the initial scuffle, while Antony — who was held outside by Trebonius (an Opportunist with no allegiance) — remained loyal to Caesar even after his death, defending him and tracking down many of the conspirators.

After a few months of playtesting, I realized I needed players to be invested in the figures/characters they were playing. The importance of players being invested in their citizens came from reading Geoff Englestein‘s book, Achievement Relocked. Now, who knows how well I understood his explanation of the Endowment Effect, but I nevertheless came to the conclusion that players needed this flavor text to understand the background of each historical figure and what made them special. More importantly, they needed abilities. With the background and special abilities, I felt I had a way for players to be invested in their unique and exciting citizens.

Each citizen has an ability that becomes available once it is revealed (a slight nod to Cosmic Encounter). Each ability is based on the citizen’s historical personage. For example, Decimus’ ability allows them to remain secretive in nearly every sense, so no one really knows their intentions; Antony, while at the Forum, can protect Caesar by limiting how players can add knives to the Curia; Trebonius can force — or help — players remain in their current locations, just like he did to Antony on the Ides of March.

Each citizen in the game has their ability that they can use to assert control over the game in various ways. Whether that control will be exactly what players wish for during each and every game is not likely, but throughout the shifting allegiances and shifting game state, players must learn how they can use their abilities to assert control as best they can. The control’s not perfect and it can be a rough edge, but it traces the historicity of the event and gives players’ a sense of agency.

The second way I tried to add control to the game were conspiracies, which eventually became the issues. Now, I also built these as a small biography of Caesar thematically: telling players why they should or shouldn’t want to kill Caesar to get them invested in the thematic and historical elements that the citizens were thinking about and feeling in 44 BCE — but I designed these effects primarily to give players an element of control.

The issues took some balancing, but also a lot of letting go of the idea that everything needed to be balanced. I think some of the most interesting games are those with excitable moments in which players are thrilled or frightened by the possibilities. The issues give players a sense of control while they hold the deck, which makes them the Tribune and allows them to break ties. Players vote between two presented issues, which change the game in different ways: some slight and some significant. This process lends itself to the information I mentioned earlier in regards to deduction, but it also lends itself equally to the social aspects. Players get a chance to voice their opinions, call out others, try to get people on your side to choose the desired issue, etc. Depending on the issue, you and your allies assert control by being able to manipulate allegiances, reveal information, give resources, or shut down locations. The control here is more subtle than before and relies on communication and other people.

The third focus to provide control is the Temple, a location in the game where players can go to sway themselves and change their own allegiances. Players must burn a card from their hand, but once they do, they’re allowed to play a sway on their own citizen or burn a sway from their own tableau. With the Temple, it doesn’t matter which citizen you’re dealt at the beginning of the game. You can start as Marc Antony and personally be determined to kill Caesar, so then all you need to do is work toward adding knives to the Curia, then visit the Temple to make sure your allegiance matches your goals. Obviously, this isn’t as easy as it sounds, but I have to leave some things up to the experience of the game, right?

Control is hard. Like I said before, games are a way for me to find solace in facing whatever is going on in the real world, providing respite and giving me some illusion of control over moments. 23 Knives, in a way, gives me that same sort of control, but I hope it can also help remind me that I can also let go, change my path, get swept up in history, and still be happy (or at least accept) the experience.

/pic8500388.jpg)

/pic8762160.jpg)

/pic2576459.jpg)

/pic8388892.png)

/pic8388893.png)

/pic8388894.png)

/pic8388895.png)

/pic8388896.png)

/pic8762164.jpg)

/pic8388897.png)

/pic8762161.jpg)